Coccidiosis is of universal significance in poultry production causing devastating losses due to a large number of birds per flock and high stock densities. The economic impacts of coccidiosis are: decreased profit caused by higher feed conversion, growth depression, increased mortality and the costs of prevention or treatment. Worldwide the annual costs inflicted by coccidiosis to commercial poultry have been estimated at € 2 billion.

The traditional control of coccidiosis mainly relies on chemoprophylaxis which appeared to be effective for the last decades. However, the increased occurrence of resistance against all anticoccidial drugs and a possible upcoming ban restricting their use have left the poultry industry with a renewed challenge for coccidiosis prevention and control via alternative strategies.

Coccidial parasites are protozoa belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa. Chicken coccidiosis is caused by seven species, all from the genus Eimeria: E. acervulina, E. brunetti, E, maxima, E. mitis, E. necatrix, E. praecox and/or E. tenella.

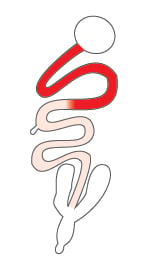

Hereby Fig 1. the Eimeria lifecycle:

Immunity

Birds of all ages are susceptible. Chickens can develop immunity after infection, however, immunity is species-specific, leaving birds at risk to other Eimeria species. Immunity to Eimeria species is acquired gradually and is not complete until the birds are 7 weeks of age – these 42 days are the critical risk period.

Immunosuppressive diseases, such as Marek’s disease, infectious bursal disease (IBD) and others, interfere with the development of immunity, and infected birds can be more susceptible to coccidiosis.

The life-cycles of these species are direct (fig. 1) . Chickens ingest sporulated oocysts (the parasite ‘egg’) from contaminated litter, and these pass into the intestinal tract, where the parasites invade the cells of the intestinal wall. Several cycles of replication occur which lead to the formation of new oocysts which are shed in the faeces. Depending on environmental conditions (including temperature and humidity), the oocysts sporulate and become infective. The entire cycle takes 4 to 6 days. This short, direct, life-cycle combined with the potential for massive replication during the intracellular phase, makes this group of parasites a serious problem under intensive farming conditions.

Characteristics of lesions will depend on the species of Eimeria affecting the intestine. Lesion scoring is a technique developed to provide a numerical ranking of gross lesions caused by coccidia (Johnson and Reid 1970). Read more about on farm gut health monitoring in our blog.

Lesions of major species

Eimeria acervulina

Severity of infection may vary with the isolate, the number of oocysts ingested and the immune status of the bird. Reduction in rate of weight gain is also proportional to the infective dose. Watery and mucoid droppings may be seen as early as 4 days post exposure. Heavy infections often cause lesions and sometimes mortality may result.

Light to moderate infections may produce little effect on weight gain and feed conversion however, may cause loss of carotenoid and xanthophyll pigments. Eimeria acervulina commonly invades the duodenal loop of the intestine and in heavy infections may extend to infect lower levels of the jejunum and even the ileum or lower intestine. White lesions of E. acervulina are clearly visible on the mucosal surface of the duodenal loop. The white streaks are oriented transversely across the intestine in an arrangement often described as ladderlike.

Light to moderate infections may produce little effect on weight gain and feed conversion however, may cause loss of carotenoid and xanthophyll pigments. Eimeria acervulina commonly invades the duodenal loop of the intestine and in heavy infections may extend to infect lower levels of the jejunum and even the ileum or lower intestine. White lesions of E. acervulina are clearly visible on the mucosal surface of the duodenal loop. The white streaks are oriented transversely across the intestine in an arrangement often described as ladderlike.

Eimeria maxima

Eimeria maxima infections are located in the midintestinal area on either side of the small node (rudimentary diverticulum) left by the yolk sac. In severe infections, lesions may extend up into the duodenum and down as far as the ileo-cecal junction. Late in the life cycle ,a few petechiae may appear on the serosal surface of the intestine.

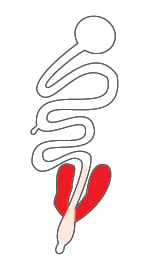

Eimeria tenella

Eimeria tenella, the well-known cause of cecal or “bloody” coccidiosis, which invades the two ceca and in severe cases may also parasitize the intestine above and below the cecal junction. Eimeria tenella penetrates deep in the intestinal tissue producing damage in the mucosa and muscular layer. The cecal lumen is filled with coagulated blood and necrotic debris.

Emeria Necatrix

Emeria Necatrix

Eimeria necatrix also becomes established in the midintestinal area. Probably because of the low reproductive capability of E. necatrix, it is not able to compete with other coccidia and is diagnosed mostly in older birds such as breeder pullets or layer pullets aged 9–14 weeks . E. Necatrix along with E. tenella are the most pathogenic of the chicken coccidia. Infection with 104–105 sporulated oocysts is sufficient to cause severe weight loss, morbidity, and mortality. Survivors may be emaciated, suffer secondary infections, and lose pigmentation. Droppings of infected birds often contain blood, fluid, and mucus. The intestine may be ballooned, the mucosa thickened, and the lumen filled with fluid, blood, and tissue debris. From the serosal surface, the foci of infection can be seen as small white plaques or red petechiae. In dead birds, these lesions appear white and black, giving rise to the expression “salt and pepper” appearance.

Coccidial oocysts are extremely resistant to environmental conditions and disinfectant agents, therefore, eradication of coccidiosis from chicken houses by litter removal, cleaning and disinfection is not feasible; so several antimicrobials or antiprotozoals have been used.

Potential methods of coccidiosis prevention or treatment:

Anticoccidial Drugs

Live vaccines

Probiotics

Immune support

Combination strategies

Anticoccidial Drugs

Anticoccidials are given in the feed to prevent disease and the economic loss often associated with subacute infection. Prophylactic use is preferred, as most of the damage occurs before signs become apparent and drugs cannot completely stop an outbreak. Continuous use of anticoccidial drugs promotes the emergence of drug-resistant strains of coccidia. Various programs are used in attempts to slow or stop selection of resistance. there is widespread resistance to most drugs. Coccidia can be tested in the laboratory to determine which products are most effective. The effects of anticoccidial drugs may be coccidiostatic, in which growth of intracellular coccidia is arrested but development may continue after drug withdrawal, or coccidiocidal, in which coccidia are killed during their development.

Antimicrobial resistance

No new chemicals have been introduced for decades and resistance has been documented for all the drugs approved for use in chickens, although the onset of resistance can be slowed by using rotation programs with different chemicals and/or ionophores . Nevertheless, resistance to the available chemicals and ionophores has become widespread . Drugs with novel molecular modes of action and hence unprecedented targets, will be necessary if control of coccidiosis by chemotherapy is to be achievable in the future.

Live vaccines

A species-specific immunity develops after natural infection, the degree of which largely depends on the extent of infection and the number of reinfections and or the status of the immune system. Protective immunity is primarily a cell mediated immune reaction; T-cell response.

Commercial vaccines consist of live, sporulated oocysts of the various coccidial species administered at low doses. Modern anticoccidial vaccines should be given to day-old chicks, either at the hatchery or on the farm. Because the vaccine serves only to introduce infection, chickens are reinfected by progeny of the vaccine strain on the farm. Most commercial vaccines contain live oocysts of coccidia that are not attenuated. The self-limiting nature of coccidiosis is used as a form of attenuation for some vaccines, rather than biologic attenuation. Some vaccines sold in Europe and South America include attenuated lines of coccidia.

Probiotics

A coccidiosis infection in poultry often leads to necrotic enteritis, as Clostridium perfringens, naturally present present in the gut, is benefitting from the intestinal damage caused by Eimeria. Consequently, it is important to manage and more importantly anticipate to the enteritis to reduce the impact on performance and general health of the birds. Probiotics, such as Bacillus spp. can be used in feed or through drinking water to prevent or even treat necrotic enteritis.

Immune support

As chickens are able to build up protective immunity after cocci infection, it is important to accelerate that process. Beta-glucans are known to have an immune modulating effect and can be a usefull tool in coccidiosis prevention. Research has shown that algal derived beta-glucan, as a feed supplementation, is enhancing the cell-mediated immune response in the gut, destroying the pathogen before severe lesions will occur. Consequently, less cocci induced lesions are observed in beta-glucan supplemented birds undergoing an Eimeria challenge. This strategy creates a win-win situation as it firstly allows circulation of oocytes (no effect on OPG counts, in contrary to the use of (chemical) anticoccidials) in the house, needed to create immunity, and secondly offers an immune modulating effect, accelerating the immune response against Eimeria.

Combination strategies

There is no silver bullet to tackle coccidiosis and to replace the use of anticoccidial drugs. Combination strategies are the way forward, and do not require a withdrawal time!

Vaccination is a good anticoccidial replacement strategy, but offers no protection against necrotic enteritis. To prevent enteritis, it is important to use a probiotic in combination with vaccination. A second, not to neglect tool to support the vaccination is the use of an immune modulator, such as beta-glucan, to accelerate the response of the immune system to the vaccine.

Replacement of anticoccidials through nutritional solutions is possible. Again a combination strategy targeting several aspects of the coccidiosis problem is needed. The best protection is observed when the solution is simultaneously supporting the immunity, preventing necrotic enteritis and is killing the coccidia (partly) still allowing some circulation oocytes to built up immunity. Several plant derived molecules offer an anti-parasitic effect and can be used as an in feed solution in combination with a probiotic and beta-glucan.

Find out how a combination strategy can manage coccidiosis in a sustainable way. We present our poster published during the WVPA on 'A three-strategy approach to manage coccidiosis'.

Our mission is to partner with you to manage coccidiosis in a natural and sustainable way!

Benefits of alternative strategies

Decreases the use of/need for ionophores

No withdrawal time applicable

Reduces the incidence of necrotic enteritis

Supports cocci vaccination

Reduces the use of therapeutics

Avoids performance reduction in case of subclinical coccidiosis

Is a natural solution for cocci management

© Kemin Industries, Inc. and its group of companies 2026 all rights reserved. ® ™ Trademarks of Kemin Industries, Inc., USA

Certain statements may not be applicable in all geographical regions. Product labeling and associated claims may differ based upon government requirements.