Read time: 10 minutes

The intestinal microbiome

Poultry intestines are colonized with a wide array of microorganisms: bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses. These are collectively known as the microbiota. One speaks of the microbiome when including also the genes and genetic potential of these microorganisms. However, in practice, both terms are often used interchangeably.

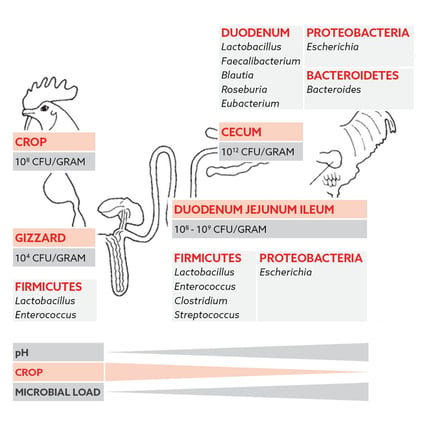

Although they are strongly interconnected, one can consider the different intestinal regions as semi discrete microbiomes. Their bacterial load and composition are determined largely by the respective physiology, digesta flow, substrate availability, host secretions, pH and oxygen tension.

Where do intestinal microbes come from?

The colonization of the gastrointestinal tract of chickens starts immediately after hatching, therefore, the environment in which hatching takes place, plays a crucial role in the development of the intestinal microbiome. The chicken production system is rather unusual as eggs are separated from the parental flocks prior to hatching. As a consequence, parental influence is significantly reduced and the intestine is primarily colonized by environmental microorganisms derived from bedding material, feed, human handlers, etc.

The colonization process itself occurs very rapidly. One day after hatching, 108 and 1010 bacteria per gram of content are formed in the ileum and cecum respectively. These numbers increase to 109 and 1012 on day three. During the following 30 days, bacterial counts remain stable however the composition changes significantly. The first bacteria to colonize the gut are facultative anaerobes, which in turn create anaerobic conditions that promote the growth of obligate anaerobes. A typical and stable adult gut microbiome is established around three weeks of age. The small intestinal microbiota are established first then the cecal microbiota. Over time the cecal community will show greater diversity.

What bacteria can be encountered in the intestine?

Almost all bacterial species in the chicken intestine can be appointed either to the phylum Firmicutes (70%), Bacteroidetes (12%) or Proteobacteria (9%).

The Firmicutes are a diverse group of bacteria with many health promoting benefits. The two most important butyrate producing families, Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae. are situated within this phylum. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an abundant butyrate producing species from the Ruminococcaceae family. In general, Lachnospiraceae are able to convert lactate into butyrate, while Ruminococcaceae cannot. Lactate can be produced by a different group of Firmicutes, namely Lactobacillus species from the Lactobacillaceae family. Also, several Enterococcus species are known to produce lactate. However, this genus also contains (opportunistic) pathogens, such as Enterococcus cecorum.

The Bacteroidetes phylum is also a very diverse group. Species such as Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron possess a wide array of enzymatic activities, which initiate the breakdown of complex carbohydrates. These breakdown products can be utilized as substrate by other species which convert them to short chain fatty acids. In addition, B. thetaiotaomicron antagonizes intestinal pathogens through a range of mechanisms activate host immune defenses and have direct interactions with other intestinal bacteria. Most often there is a trade-off between Bacteroides and Prevotella species, either one will dominate at the expense of the other.

Most pathogenic bacteria belong to the Proteobacteria phylum. Examples are Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Yersinia enterocolitica (γ-Proteobacteria), Desulfovibrio piger (δ-Proteobacteria) and Campylobacter jejuni (ε-Proteobacteria). A healthy, well-balanced microbiome is able to repel invasion and colonization of these type of pathogens. However, a perturbated balance offers opportunities to pathogenic bacteria.

In chickens, microbiome studies focus mainly on the ceca. Of all intestinal compartments, the ceca is the most densely populated with the widest variety of bacteria. Compared to the other areas, intestinal content is retained much longer, providing a niche for extensive microbial fermentation. Therefore, they are the main focus in most chicken microbiome studies.

Why are intestinal microbes of importance?

The intestinal microbiome can both be linked with health and disease. Some bacteria are pathogens (e.g. Salmonella species), others only become harmful if they get in the wrong place or proliferate in number (e.g. Escherichia coli, Enterococcus cecorum), conversely many are very useful to the host. The latter category can contribute to host health and wellbeing (i.e) by providing nutrients (short chain fatty acids, amino acids, vitamins), and/or, by programming of the immune system and/or prevention of colonization of harmful species.

The balance of benefit and harm for the host depends on the overall state of the microbial community in terms of its distribution, diversity, species composition and metabolic outputs. Imbalances can be detected for example by determining the ratio of two bacterial populations: a beneficial one, such as the Firmicutes phylum, and one that poses potential risks, such as the Proteobacteria phylum.

Antibiotics: friend or foe of the intestinal microbiome?

Antibiotics are efficient in killing of infectious bacteria, however, they do not only act on bacteria that cause infections but also affect the resident microbiota. It has been shown that treatment with antibiotics can decrease the taxonomic richness, diversity and evenness of the community. Some bacterial groups may be able to recover, others do not, and this may shift the previously established balance in a detrimental way. Owing to the close links between the resident microbiota and the host, such disturbance of balance can potentially affect host physiology and health.

What can we do to keep the intestinal microbiome in good shape?

Feed is a primary compositional driver of the intestinal microbiome of chickens. More interestingly, it provides opportunities to steer and manipulate the intestinal microbiome in an elegant way. This is where pre- and probiotics can play their part.

Pre- and probiotics are often, and successfully, applied to improve or restore intestinal health. Benefits of pre-/probiotics include improvement of gut barrier function and host immunity, reduction of potentially pathogenic bacteria and the enhancement of SCFA production. They are a convenient way to help restore the balance whenever the intestinal microbiome is challenged, or mitigate a challenge occurring impacting profitability.

Typical signs of a disturbed intestinal microbiome:

- Intestinal inflammation

- Diarrhea, wet litter or foot pad lesions

- Poor animal performance

- Manifestation of (opportunistic) pathogens

We share with you some very interesting insights and learnings from Aaron Ericsson who gave a presentation on 'A gut feeling: comparative metagenomics in Veterinary and Human health'. Watch the entire presentation by clicking the button below.